Originally published on VanWinkle's (March 2016)

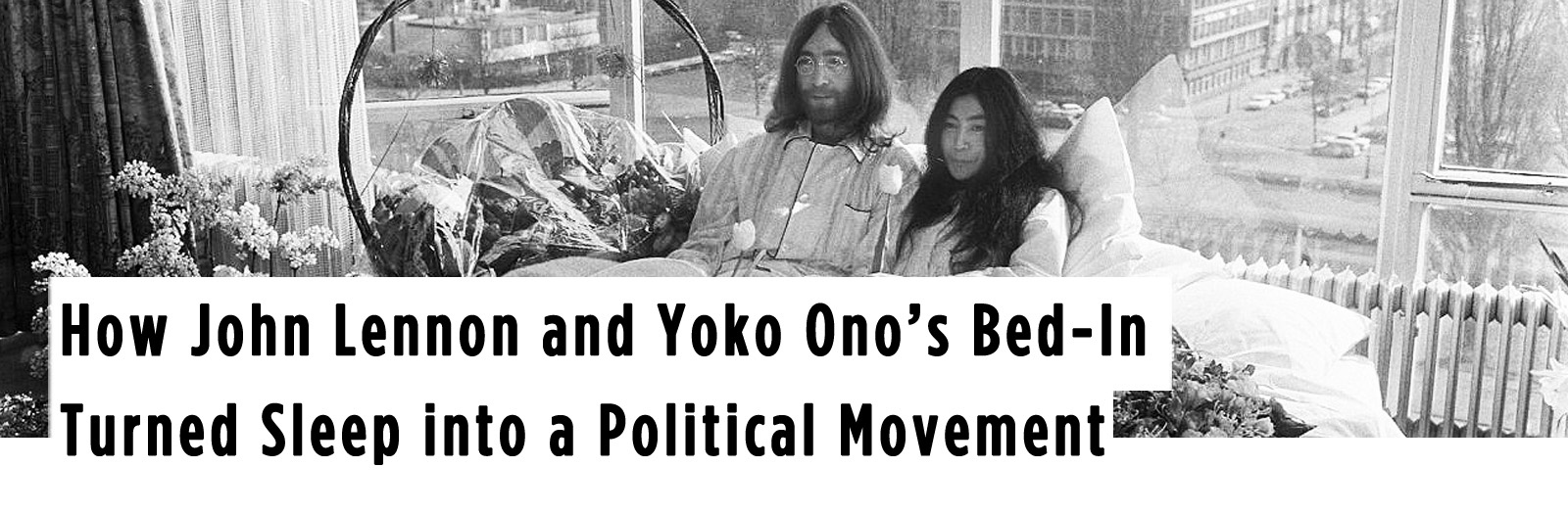

On March 25, 1969, John Lennon and Yoko Ono were married, took to their bed and invited the international press to join them. This was not an attempt to broadcast live televised sex, but, a well-orchestrated form of social protest. The newlyweds promoted their “Bed In” at the Amsterdam Hilton to rail against the Viet Nam War.

Ono, clad in a white nightgown explained to reporters:“We thought that Amsterdam was a very important place to do it because it has a very fresh and alive interest. And we’re thinking that, instead of going out and fight and make war or something like that, we should just stay in bed — everybody should just stay in bed and enjoy the spring.”

Lennon and Ono then moved their encampment to a Montreal hotel and continued to garner attention for the anti-war cause. They even recorded “Give Peace A Chance” in the hotel room.

The famous couple’s mattress-based act of rebellion has become an indelible part of pop culture. What might have been perceived at the time as an indulgent bit of showmanship resonates with artists and musicians around the world decades later. Even the ephemera from those weeks in bed retain value. The handmade sign which hung above John and Yoko’s bed fetched $154,000 at Christie’s auction in 2011.

Why did this mellow form of rebellion resonate, where did it come from and what other political statements can be made effectively on top of a mattress?

Bed-Ins may be the lazier grandchildren of Sit-Ins, during which demonstraters sat in front of or inside a government agency, private business, university or other building to express dissatisfaction with the status quo. One of the most famous examples comes from the Civil Rights era, when four African American students from North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University walked into a Greensboro Woolworth’s counter, asked for coffee and, when refused service based on a whites only policy, patiently remained seated and waited for the world to watch.

Mohandas Gandhi, in his efforts to gain independence from the British, employed similar forms of non-violent resistance. He was greatly influenced by his mother who stressed non-violence, vegetarianism, fasting for purification and respect for all religions. Further along in his life, Gandhi read Thoreau's “Civil Disobedience” and was inspired by the notion of non-violently refusing to cooperate with oppressive governmental regimes and policies.

Lennon paid homage to these early civil rights activists as dozens of reporters gathered round his bed. Chillingly, his words portended his own tragic future. “No one’s ever given peace a complete chance," he said."Gandhi’s tried it, Martin Luther King tried it, but they were shot.”

Artists, inspired by Lennon and Ono’s protest, reimagined the Bed-In. For example, Billie Joe Armstrong, lead singer of Green Day, and his wife, Adrienne “performed” a similar bed-in with a poster above their heads reading "Make Love Not War" in Spanish.

But Lennon and Ono’s Bed-In reverberates most in the world of political protest, most notably the “occupy” movement which by definition takes one’s sleeping outside for everyone to see. Between 100 and 200 protestors slept in Zucotti Park as the Occupy Wall Street movement took hold in September, 2011. Tents were not allowed at first so protesters dozed in sleeping bags or under blankets. Whatever mode of equipment they used, the protestors drew attention to themselves day and night, awake and fast asleep as their continuous presence created a ripple that spread through the U.S. and the rest of the world

As activist Nancy Schimmel noted of her involvement Occupy Oakland and Berkeley, sleeping at Occupy had two functions. “One was to emphasize that people were losing their homes in the ongoing economic crisis, and living in tents," she said. "The other was to build community. People woke up and stood in line for the port-a-potties together, talked, ate together, talked some more, picked up trash, met to deal with encampment issues, planned actions.

Occupy Wall Street Protesters, Wikipedia

But communal sleeping space was not just a matter of good vibes. It raised a serious legal issue: Is sleeping overnight in public spaces a protected form of free speech under the U.S. Constitution?

An attorney representing the Occupy Wall Street protesters claimed at a hearing before a judge: "It's not a camping case, it's a First Amendment case. They're sleeping there 24 hours a day as a form of expression." Legally, the argument had a leg to stand.

Back in 1984, protesters petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court for the right to sleep overnight on the National Mall in Washington as a way of calling attention to homelessness. In that case, the court did not actually decide the question of whether sleep was a protected form of speech, but the issue continued to crop up.

In 2000, a federal judge ruled that a tenants' advocacy group had the right to sleep overnight on sidewalks near the mayor's home to protest proposed rent increases for rent-stabilized apartments. Still, the question of whether sleeping is truly free speech has yet to be answered by the courts as the issue was sidestepped once again.

More recently, a “sleepover” protest organized by comedian Russell Brand took place at an occupied housing project in North London after residents were pushed out to make way for redevelopment. Brand announced that he’d be spending the night in a sleeping bag to bring attention to “social cleansing.”

Some protests don’t actually involve beds or sleeping bags, but do require linens to make a point. When parents of high school students at the Montgomery County Public Schools got tired of a pre-dawn wake up time so their kids could get to school 7:25am , they organized a “sleep in protest.” The group called “Save Our Sleep” gathered in front of the school system’s Rockville, Maryland headquarters with blankets and pillows to make a point. They claimed that sleep deprivation leads to depression, obesity, migraines, car accidents and poor academic performance.

Bangkok, Thailand, January 13, 2014 : Tent protesters to stay overnight at MBK, Pathumwan intersection in Bangkok, Thailand. iStock by Getty Images

Political expression takes many forms. But what if we have no other choice than to be in bed as the result of illness or a disability, but still want to make a statement? What if we aren’t famous enough for anyone to arrive at our bedroom and interview us about our world views?

The so-called “Sick Woman” Theory espoused by Johanna Hedva claims, among other things, that if “political” means any action that is performed in public, doesn’t that exclude a lot of people — bedridden, imprisoned, caregivers, or otherwise disabled — from engaging in social discourse?

"If being present in public is what is required to be political, then whole swathes of the population can be deemed a-political – simply because they are not physically able to get their bodies into the street," she eloquently states.

Specifically Ms. Hedva explains that her chronic illness prevented her from attending the “Black Lives Matter” protest which took place close to her home. Struggling to be present in body at the gathering, but physically unable to attend, Ms. Hedva assesses her conundrum. “As I lay there, unable to march, hold up a sign, shout a slogan that would be heard, or be visible in any traditional capacity as a political being, the central question (is): How do you throw a brick through the window of a bank if you can’t get out of bed?

In some way Sick Woman Theory empowers those resting or sleeping in bed. She brings attention to those who want to be heard even if they can’t be seen in the crowd.

All of this, in some way, traces back to Lennon and Ono's Bed-In. Even if their statements were a bit toothless, they were pioneers as they crooned, drew pictures and sometimes even slept. Fans and haters alike could not help but take notice of the quiet revolution they began in a bed.

While it may at first seem like a slacker way to change society, in some cases, bed-in and sleep-in protests have actually worked to bring attention to injustice, war and, for that matter, asking kids to get up too early. Who needs fiery speeches and picket lines anyway? In the right setting, the bed might be mightier than the crowd.