Originally published on Bookslut (November 2006)

At a crowded cocktail party in a New York apartment filled with Inuit totems, hand-tied rugs and dimmed brass floor lamps, I am doing my best to mingle with the sea of new faces. The mothers and fathers of my daughter?s private school kindergarten class are arriving for the first get-together of the academic year. They chit chat, sipping Merlot, handling sushi, rubbing silk and pinstriped shoulders. My husband is home babysitting. I am uncomfortable and alone, but want to mix with the crowd, so I do what makes me feel comfortable. I start talking about books. And in this setting, the topic narrows to children?s books.

"Isabelle told me that her teacher was reading The Magic Finger to the class," I say to a wide-eyed mother with a pixie haircut.

"I didn't know about that," she replies.

Another woman in a black turtleneck remarks over my shoulder, "My daughter never tells me anything about what's happening in school."

"By Roald Dahl?" the pixie asks -- then answers herself, "Yes. I loooove Roald Dahl. My mom used to read Charlie and the Chocolate Factory to me every night before bed."

"My father just sent me all of my books from when I was a kid," the second woman says between gulps of Diet Coke. "I got such a kick out of seeing them again and reading them to my son -- Horton Hears a Who, Make Way for Ducklings, Caps for Sale. Those were my favorites!"

"Isn't it wonderful reading books to our kids again that our parents read to us?" the first woman pipes in.

I nod agreeably, but the truth is growing up in my blue-collar neighborhood, there were no books in my house. I don't remember a single Dr. Seuss, Margaret Wise or A.A. Milne. Of course, the Philadelphia Free Library loaned books, but I'm talking about the age when I couldn't get there by myself. And the busy adults and distracted older siblings around me were not going to take me either. I do not remember being read to at all.

I wasn't alone in not having books. Reading to children was not a priority for the parents in my community. My friend Debbie, who grew up close by, told me that she was astonished to learn that her husband (not from the neighborhood) was read to as a child.

Both Debbie and I come from Italian-American homes, which, according to writer Gay Talese, may explain our shared experience. In 1993, Talese published an essay for The New York Times Book Review in which he recalled having little in the way of books. He wrote, "popular classics in children's literature were rarely found in Italian-American homes." Talese also lamented the common loss of "pre-adolescent bonding with the wondrous figures described in children's books" among the Italian American community. Talese's explanation for this phenomenon cites, among other factors, the influence of history, superstition and prejudice.

Other circumstances beyond class and ethnicity can limit a child's exposure to literature. Child psychiatrist, Edward M. Hallowell, author of The Childhood Roots of Adult Happiness wasn't read to as a child because of his mother's mental illness. Dr. Hallowell encourages parents to read to their children because it creates a "connected childhood," which in turns leads to a happier life. But he adds that missing out on books as a child can have unexpected benefits. When he admitted to a college professor that he had not yet read a classic book, he anticipated being criticized. Instead, he was surprised and invigorated by his teacher's response: "Aren't you lucky. What enormous pleasures you have in store for you someday."

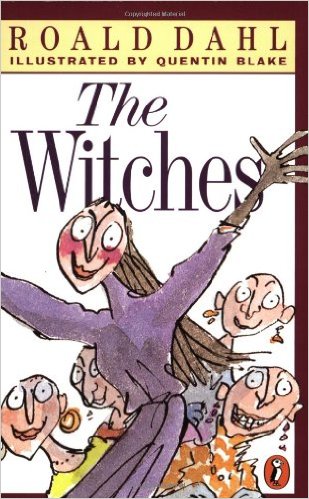

I agree. What Mr. Talese may consider a loss has been nothing short of a fairy tale ending for me. What could be viewed as neglect has turned into a blessing -- even though it took me 40 years to recognize that. Discovering children's books that I never experienced as a child opened doors of unexpected joy. By experience I mean more than reading the words on a page. Good Night Moon's reassuring verses and the coos of my infant daughter soothed my jangled post-partum nerves. My fingers moved acrossPat the Puppy's fleecy fur and Daddy's scratchy beard -- as if I were reading Braille. I grooved to the irresistible rhythm of Chicka Chicka Boom Boom and One Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Blue Fish with my two-year old son. I learned that a good children's book is like a poem -- concise, unsentimental, affecting. That children's books fail when they underestimate a child's lightning quick judgment for boring or a stupid ending, something that even discriminating adult readers often take longer to recognize. I am astonished at my emotional reaction to The Runaway Bunny, Are You My Mother? and Love You Forever only possible in the exquisite grip of parenthood. With some books, I am caught completely off guard, surprised at its emotional impact on me. Tears welled upon reading the last pages of Dahl's The Witches when the narrator, a boy-turned-mouse and his elderly human grandmother, both realize that they have the same short numbers of years left, by reason of old age and a rodent's lifespan respectively. My daughter snapped me back to reality, clapping the cover closed with a smile and reaching for another book, unfazed.

Anticipating an ending too sad or disturbing for the age of my children, I have taken literary license.

"So the little girl fell asleep in the snow and dreamed about stars," I ad libbed from "The Little Match Book Girl" with apologies to Han Christian Andersen.

I feel lucky. That I didn't enjoy the elegance and power of The Snowy Day until 1996, that I don't know (still) how The Little Prince ends; that I only vaguely recall Where the Wild Things Are as a cartoon on TV; that I could hope, along with my daughter, that Louis, the mute bird in The Trumpet of the Swan would be able to save enough money to re-pay his father's debt. I am grateful that I can marvel with my grown-up mind at Leo Leonni's bright collages, aware as an adult that his simple arrangements of paper and color unearth layers of meaning. That Leonni's life lessons about loss, renewal and change in The Little Seed remain true and worthwhile.

As I left the party that night, the streets were wet from an earlier autumn rain. The lamplights reflected a smear of yellow on the streets. I hurried home to put my daughter to bed with a new book I had found at the library that day -- a book I never missed.

There are pleasures still in store for me.